Our erotic desires are a

pull towards healing. While bodily pleasures are appealing in their

own right, our specific emotional needs determine the focus of our

sexuality. Intercourse with the opposite sex may be the most

natural way to procreate, but most of our sexual behaviour is not about

breeding. A desire for a healing of the psychological tear between

the masculine and the feminine underlies heterosexual behaviour.

Exclusively homosexual behaviour in males might be driven by a desire

for a healing between the individual and the patriarchal society.

Lesbians seek healing away from the more troubled masculine psyche

and in bisexuality we may see a less neurotic, less fixated, form of

sexuality in which the sharing of sexual pleasure is not restricted

by the gender of the participants.

Often we also have sexual

fixations around particular situations or kinds of activity. The

erotic is like an ambulance crew which goes straight to the

spot where we are most wounded.

I'll first use myself as an

example. During my early adolescence I developed a strong sense of

shame about masturbating. This can't be attributed to any messages I

picked up from my parents, but may have been a response to the way

that other boys joked about the act as if anyone who did it was

pathetic. The point is that I went for about six months without

masturbating and felt that a black cloud of shame was hanging over my

head. Eventually I talked about this with my parents and they

reassured me that masturbation was perfectly natural and that I had

done it when I was a baby. So I went back to masturbating, but in

later years I still felt uncomfortable about how women would view me

if they knew how much I did it.

Later, as I began to explore

my sexual fantasies and eventually began to write erotica, I found

that one of the things which gave me intense pleasure was the idea of

a woman watching me masturbate. Here we have an example of the erotic

as a process of healing. What was most erotic was a sexual

transaction which reassured my deep-seated fear of rejection.

I recently read an account

by a woman, who had been raped and who writes erotica, of how writing

a rape-based story helped her to take back ownership of her own

sexuality. And another woman who suffered a similar trauma has told

me of how rape-play with a sexual partner is extremely erotic for her

as long as she feels safe.

This fits with the idea that

erotic desires and erotic fantasy represent a process of healing of

our deepest wounds.

But does our society

facilitate or hinder such healing?

Trauma lies not so much in

the things which happen to us as in the way we think about those

things. Many individuals go through very scary or painful experiences

and then more or less forget about them as soon as they are over.

Giving birth tends to be very painful and I'm sure it can be a

frightening experience when it occurs, but once the mother has a

healthy baby in her arms it seems to be quickly forgotten. What makes

for trauma is on-going questions like : “Was it my fault?",

“What will people think?", etc.

What is needed to heal

trauma is self-acceptance – the realisation that what happened

can't be changed, that whatever one feels is always all right and a

trust that the mind knows the way towards healing. Erotic fantasy

need not be a part of that, but for some of us it is, and this needs

acceptance.

Prevalent social beliefs can

work against this process. In the case of rape or child molestation

an emphasis on the need to condemn the act and the perpetrator can

lead to a feeling that the survivor of the abuse should remain in the

role of victim. The act of finding healing and renewed confidence

through fantasies which eroticise the experience may be viewed as a

retroactive condoning of it. But really this has nothing to do with

the fact that the abuse was wrong and can be criminally prosecuted.

When it comes to trauma

resulting from sexual abuse part of the suffering is bound to come

from the sense of shame which accrues even to the victim in a society

which still carries a deep-seated fear of sexuality. We often think

differently about someone who has been raped than we do someone who

has been stabbed, and yet both are violent acts in which the body is

invaded.

It might seem strange to say

that our society has a deep-seated fear of sexuality when we look at

what shows on television and the easy access to porn on the internet.

But sex is not treated simply as the pleasurable physical act which

it is. In polite society you can say you just drank a really nice cup

of tea, but try saying you had a very satisfying masturbation session

last night. Why should the two be any different? Only because we live

in a society founded on the repression of sexuality and which, thus,

rightly fears the power of sexuality to disrupt it. In and

of itself an act of sexual intercourse is like dancing, a pleasurable

physical activity involving intimacy between two or more individuals.

But you can dance in public and you can't have sex in public. And in

the media, nudity and even loving sexual behaviour are treated as if

they were more offensive to our deeper selves than violence is. They

aren't. Loving sexual interactions, heterosexual or homosexual, are

perfectly in harmony with our deepest nature which is to be

unconditionally loving. Violence runs against that nature, but its

depiction in the media plays an important cathartic role in our

neurotic society. The reason why nudity and sex, when not aggressive

or abusive, are treated as something dangerous is because these

things are dangerous to our neurotic selves. They are not dangerous

to non-neurotic adults or to children who have not yet become

neurotic. But it is those who are particularly neurotic who impose

the fear-driven rules of society.

It is important to be

understanding about this fear of sex. Someone who is homophobic has

no more choice about the fact than a arachnophobe has about being

scared of spiders. In both cases they can learn to be free of fear,

but it requires sensitivity on the part of those who are trying to

help them.

And, of course, sex can have

a dark face when combined with neurotic armouring. There is nothing

wrong with enjoying fantasies about raping people, but to do the

thing itself is evil. And some adults use their position of authority

over children to satisfy themselves sexually. This is only the most

socially-unacceptable form of abuse of adult authority over children.

Being indoctrinated into a religion, being forced to perform in child

beauty pageants, being told they are expected to go into the family

business - any of these things, and many more, can have as big a

detrimental effect on a child's life as an adult as sexual abuse. In

general, to teach a child to obey authority because it is authority

(“You'll do it because I say so.") is to lay down the

conditioning which can make the child a future victim of other

authority figures, be they dictatorial politicians or sexual

predators. Once again, it is our society's fear of sex which leads us

to concentrate our outrage on the sexual abuse of children and ignore

or even condone other forms of abuse.

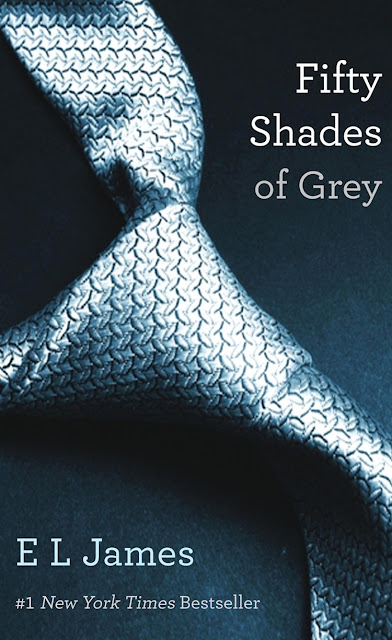

If our sexual fantasies are

leading us toward healing, then what is the meaning of the current

popularity of fantasies revolving around bondage, discipline and

sado-masochism? These fetishes are nothing new, but the bestselling

novel Fifty Shades of Grey by E. L. James (which I haven't read)

is taking the world by storm, indicating that these kinds of

fantasies are now a part of the mainstream.

One way of looking at the

erotic appeal of bondage and discipline is that, if someone is

fearful of their own erotic desires, the sense of safety that comes

with being in bondage or submitting to another's discipline, allows

them to explore those desires without danger of a scary loss of

control.

But maybe there is another

interpretation which can be put on this kind of fantasy. If the

erotic offers a path out of shame or trauma, through returning to the

source of shame or trauma and eroticising it, then perhaps we

eroticise bondage and slavery as a path to freedom from the bondage

and slavery of our neurosis.

You can also find this post on the

How to Be Free forum

here. You may find further discussion of it there.